Letters, Points of Interest, Week in Review, Back Issues, Advertise, Contact, Subscribe/Unsubscribe

A CLOSE LOOK AT PICTOMETRY

.

The Company

I met with Julian Rathnam, Pictometry's District Manager for the New England Region, who gave me the guided tour of Pictometry's imagery and software. He started with some background on the company. The company was founded in 1998 based on an idea that was formulated at the Rochester Institute of Technology in 1995. The idea was to be able to see the world from georeferenced angled views, like people are used to seeing it, instead of the straight down views that were available at the time. Pictometry's patent, which stems from the academic work, details what is now the company's data capture methodology (more on that later).

The company is privately funded and has a mix of technology and business people on the board. Pictometry started offering products in 2000 in a low-key way. Rathnam didn't apologize for the quietness of the company, but reasoned, convincingly, that this was simply a conservative move in the face of dot-bomb years in the new millennium. Recent coverage in several newspapers and on TV, as well as the company's willingness to meet with me, make it clear that the company is ready to tell its story a bit more widely now.

The Imagery

�  |

Rathnam broke the company's offerings into two key parts: the images it captures and provides, and the software tools offered to exploit that imagery. Let's start with the imagery. The company cleverly uses common terms to describe the resolution of the imagery: "community" means two-foot ground sample distance, "neighborhood" means six-inch ground sample distance. Those digital images come in two flavors: standard orthos (which can be provided by nearly anyone) and oblique images (taken at an angle, which are less widely available). The orthos are nadir images (taken "straight down" from the plane), and obliques are taken at a 40 degree angle. For those exploring oblique imagery, one important aspect is the direction from which images are taken. In other words, which sides of the buildings are users going to see? The "basic" package at the community level includes imagery from perpendicular directions, so users see two adjacent sides, as the figure at left highlights.

�  |

The choice of direction is determined by the flight plan, which is, in turn, determined by the shape of the area to be covered. Said another way, Pictometry decides the directions. The neighborhood obliques are taken from opposing directions, as the figure at right shows, again determined by the shape of the area to be covered. If the customer prefers, Pictometry will fly the "other two" directions at either level at an additional cost.

The Software

In and of themselves, the images don't sound that exciting, but it's the software, and what it can do with the images, that gives the company the deserved "hot" reputation it has acquired thus far. First off, the interface of the software, called Electronic Field Study (EFS), is slick. The main pane of the Windows-based product holds the image or map that's under consideration. Click on a point in the main image and a list of thumbnails of images that contain the point populates a tall, thin, right hand pane. If you have a whole set of orthos and obliques for an area, this can mean a large number of images! Pictometry also delivers images similar to the Digital Orthoquads (DOQs) provided by the USGS. Users can add any imagery into the image library as long as the data is geo-referenced.

�  |

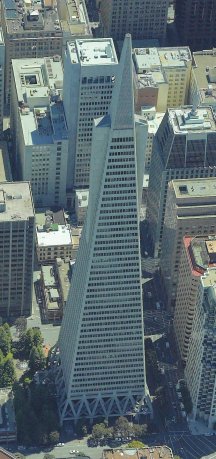

Each image produced by Pictometry, whether ortho or oblique, is geo-referenced at the pixel level. So, if you click on an oblique, like the community level one at left from San Francisco, you can get an accurate x,y location. That ability is what powers the rest of the "magic" in EFS. The magic, in reality, involves cameras, ground truthing, an inertial measurement unit (IMU), and some specialized software.

Each image thumbnail is accompanied by its name (a code that distinguishes between community and neighborhood images, orthos and obliques, and provides the date of flight) and a compass rose. I quickly learned that the compass rose is very important. For orthos, which are by definition "north up," north is at the top of the rose and south at the bottom. So, as Rathnam explained, we are sitting in the south, looking north. This is more important with obliques. For them, any near-cardinal direction will be on top, making it clear which way the camera, and thus the viewer is looking. While users may rename images according to their preferences Rathnam said that once they get the hang of the coding and the compass rose, most users choose not to change them.

The opening image for a county image library, for example, is typically a raster map of the area. From there a user can drill down, point-by-point, image-by-image, to find the area of interest. It's very intuitive, although it involves much pointing and clicking. (It reminded me of "hunt and peck" typing.) That said, the images are compressed and came up very quickly on the P2, 1 Ghz laptop Rathnam used. The company defines a minimum hardware requirement of a P2, 500 Mhz machine with 128 Mb RAM, but suggests 256 Mb of RAM. Images used in Arlington County, Virginia, were specially compressed from about 18 Mb to 1.5 Mb. Most images run about 3-6 Mb, once compressed. The image from which the neighborhood oblique image below was derived, weighed in at 6 Mb.

�  |

There is another way to get around the database of imagery which depends on "geocoding." Rathnam made it clear that this works only if the geocoded data is provided by the client. He showed me a demo of Arlington County, home of the Pentagon and Reagan National Airport. The county provided point geocoded addresses (that is, each address had a point linked to its street address in the database). So "geocoding" didn't mean creating an x,y from a surrogate (like interpolating from address ranges, which many of us consider "geocoding") but rather doing a database search and showing the result on the map, and, in turn, the images that contain it. It was fast and clearly would be helpful for emergency response-type applications.

EFS can input vector data from a GIS. And, it's possible to take the Pictometry images out to a GIS, too. One of the video clips Rathnam showed included an analyst using EFS on one monitor and something that looked like ArcInfo on the other. Rathnam makes it clear the technologies are complementary, and that Pictometry is not in the GIS business. The company is pursuing relationships with ESRI and others (more on that later).

The Magic

Once the image of interest is on the screen, it's time to do work. Rathnam grabbed an ortho and measured the distance from the pitcher's mound to home plate at a baseball diamond. The actual distance is 60 feet 6 inches. Our measurement was 60 feet 5 inches. (This was zoomed out so we didn't identify the exact pixel that contained the "rubber".) Rathman assured me that if you zoom in and select the "right" pixel at each end of the line (the rubber and the plate) the measurement is even better. The tools are designed such that measurement can be made while transparently zooming between the points during the measure command.

Next, we looked at an oblique and measured a light pole. The height was just about right. The program uses two different tools (and two different algorithms) to measure distance on the ground and height, which makes sense. You can also digitize an area on an ortho or oblique to get a square mile measurement, which can be changed to whatever units you need.

Accuracy

That brought us to a discussion of measurement accuracy vs. positional accuracy. The former is pretty good as I described in the baseball diamond example. Positional accuracy varies based on the granularity of the surface used to create the image. A coarse DEM will yield 2-5 meter accuracy, while a detailed DEM, as from LiDAR, will yield sub-meter results.

Users and Uses

Pictometry is taking its offering to two key areas: public safety (police, fire, emergency response and such) and assessors. There is a great deal of interest from regional planning agencies. Here in Massachusetts, despite interest from a variety of players, it was Mass Highways, a statewide planning organization that funds regional planning agencies, which had the money and stepped forward to set up a contract, for $1.86 million. That contract provides imagery and software for use by all state and local governments. Pictometry expects the data capture to be completed this spring with final delivery soon afterward. Weather interfered with the original plans to have the project completed last year.

Emergency responders are quick to see the value in the system. State police immediately realized it would have helped in a situation where the first floor was the first floor on one side of the building, but the second floor on the other. That information was not available to firefighters trying save colleagues who identified themselves as being "on the first floor." In Connecticut, a helicopter coming to aid State Police officers got caught in power lines causing two deaths. While it is not certain that Pictometry's database would have prevented these tragedies, responders see the value of having more information at hand.

Pictometry is also available for non-emergency situations, such as planning a sting operation. Police can see which houses or foliage can be used to hide surveillance teams. Large events, like marathons for example, can use the images to plan crowd control. One county uses the images to find safe distances for attendees at fireworks shows. Assessors in Florida are using the images to check out false claims for exemptions. The imagery went to court with the assessor after a landowner protested the denial. After one look at the printed image, the judge sided with the county. One assessor found a whole fleet of air conditioners that did not have permits.

Licensing

Rathman suggested that the company's prices for imagery were quite competitive, even with the software and obliques. But the imagery is licensed. That means that if an organization wants to re-up in two years, it reinvests the same amount (roughly) for updated imagery. If the organization chooses not to re-up, it can negotiate to license the existing imagery in perpetuity. My hunch is that this licensing arrangement may allow the company to offer rather aggressive pricing.

The Business Side

A Solution for Civilians

To get the business side of the story about Pictometry I spoke with Dante Pennacchia, Sr. VP of Sales & Marketing, and Scott Sherwood, Vice President of Marketing Initiatives. Several words and phrases permeated their discussion of Pictometry: "point of contact," "civilian," "as we normally see it." These all highlight how the offering is positioned.

Pictometry is meant to be used at the point of contact or need, which may be a dispatcher, a police officer, an emergency responder, or an assessor, in a call center, a police car, at an accident scene, or in the office, respectively. The "civilian" part of the equation refers to the fact that these are not specially trained GIS or geospatial professionals. Pictometry's imagery and software present the world in the same way that people see it everyday, from an oblique perspective (thus the term "as we normally see it"). This means that there is little training in interpretation and that these professionals can see the immediate use for the imagery. Perhaps that's why sales tend to move very quickly.

Pictometry and GIS

�  |

I asked about the relationship between Pictometry's offering and GIS since I noticed a GIS system sitting alongside EFS in one of the videos. Sherwood makes it clear that the offering is not meant to replace GIS or existing imagery, but rather to work with it. He is the first to say that organization should not toss out their orthos, like the neighborhood one at left, which Pictometry produced, but rather add to them.

Two special facets of Pictometry distinguish its obliques from traditional orthos. First, it makes "night into day." As an example, Pennacchia suggested a helicopter pilot searching for a landing site at night. Orthos will certainly show some features and open areas. They will not, however, show powerlines, or note their height. Those same powerlines are also nearly invisible in the night sky. The other is that orthos are typically taken "leaf off" so that buildings, curbs, and details can be seen. Pictometry generally flies during "leaf off" also, but can do both "leaf off" and "leaf on" in a single library. For example, by flying "leaf on" in the communities it can provide county planners with beautiful images of places to entice new business to the county, while still showing the curbs, buildings, and fire hydrants with six-inch pixel resolution in a "leaf off" environment.

The company's solution provides "an added ingredient" to GIS, Pennacchia offered. Pictometry works with GIS by working with partners. The project furthest along is with ESRI. It's possible now to use an ESRI product to locate a point of interest, pass the coordinates to EFS, and bring up images that include that point. While that's a rather loose connection, down the road the plan is to develop an extension for ArcGIS that would put EFS functionality right inside the software. Pennacchia shared that Pictometry is also talking to other GIS and CAD firms about this type of solution, including Autodesk, Intergraph and vendors involved in appraising, and 911 dispatch solutions.

Pennacchia went on to explain that GIS organizations that implement Pictometry find that it "expands the responsibility of the GIS people." (I immediately pictured an even more overworked GIS staff!) In fact, Pennacchia suggested that the data available to the GIS departments' constituents is more useful, and that the operators need less training. That turns into more support for the GIS department, which in turn, he suggested, makes GIS and GIS departments more important overall to their communities.

One constituent of local, state and federal governments are citizens. "Lay" citizens grasp the visualizations easily and find the images easier to decipher than maps or orthophotos. This idea, making imagery accessible for both citizens and professionals, is what Pennacchia refers to as "democratizing visual intelligence."

Funding and Finance

I asked about how the now cash-strapped counties and states could afford both GIS and Pictometry. I suppose I was thinking funds would come from the same budgets. Pictometry's experience is that once the agencies of a state or county see the solution, money can be freed up from individual departments, such as 911, appraisers, economic development, police, fire, district attorneys and others.

Pictometry's business model, in which the company owns the imagery and users license it, has some interesting ramifications. First off, there are no "per seat" sales. The imagery is licensed with the software to a site: a company, a town, a county or a state. That means, in Pennacchia's words, "everyone from the janitor to the governor can use it." It also means that Pictometry can resell, or re-license the same imagery to more than one client.

What's Next?

What's next for Pictometry? The company is continuing its work on integration with GIS packages and has been researching change detection functionality. From emergency response, applications will expand into natural resources management areas such as agriculture and tracking coastal erosion. Finally, expect to see more of Pictometry. The company is looking forward to exhibiting at this year's ESRI User Conference.

GEOMEND TAGGINGS PUTS LOCATION INTO HTML

.

Metamend is positioning its new HTML tagging process, Geomend, which puts latitude and longitude into the HTML of webpages, as the next standard. For the "standard" to take off, it will be necessary for those who host webpages (like your company or organization) to put the tag in, and for the search engine companies (like Google, AltaVista, etc.) to use and recognize it. Metamend also hopes to partner with telcos, wireless, and location-based services providers to drive use of the tags.

Metamend focuses on search engine optimization and promotion technologies, strategies and solutions. Basically, it provides a service that visits your website monthly and makes it more attractive to search engines. The geographic element is a new addition, first announced in February of this year. While this implementation is new, several search engines already provide location-based searches. The company plans to offer the tagging as an extra value-added service to new customers, but will offer it free to existing clients.

Tim Mayer, vice president of FAST Web Search, a partner with mobile phone provider Vodaphone, is apprehensive about the future of Metamend. "Unless it's a product that everyone uses, I don't see it being useful," he said. "You need an independent agency or large company to push a standard."

I contacted Metamend for further details about the geocoding process and the "openness" of their tags, but did not receive a reply before press time.